This piece captures what I’ve learned while going down the rabbit hole to understand how asyncio works in Python. While a few others had written on the subject, I think it is still valuable to contribute another angle of introduction, as learners with different backgrounds resonate better with different motivations and styles of explanation. This is one I’ve written for my one-year-younger self.

Why this matters

As an AI researcher, I spent most of my career focused on models and data. When it came to optimizing runtime, whether for data processing or model inference, I typically relied on batching or multiprocessing. I had very little exposure to asynchronous execution, and I didn’t think I needed it. That changed when I stepped into the world of scaffolded LLM systems.

In this space, optimizing performance isn’t just about speeding up a singular step. It often involves managing complex functions made up of many LLM inferences, some of these depend on each other; and many don’t. That’s when I began to appreciate the power and elegance of asynchronous programming.

Most of us rely on external compute when calling LLM APIs. When we make a call to a model, our program typically blocks, waiting for the remote system to respond before continuing. But if you think about it, the actual computation is happening elsewhere. Your machine is just waiting, doing nothing. Couldn’t it do something useful in the meantime? That’s exactly what asynchronous execution allows. You can kick off a request, move on to non-dependent tasks, and come back to the result once it’s ready. It’s a bit like playing Overcooked: while you’re waiting for the meat to cook, your hands are free. You might as well chop vegetables or get the plates ready.

In Python, the tool that makes this pattern accessible and powerful is the asyncio library. In this post I will walk through how to write program with asyncio, how this library works and when does it make sense to use it.

Async way of writing your python program

Applying async to flat hierarchy function calls

Now let’s start with a very simple program where we make several independent LLM API calls. I will use Groq API and openai-python library to access an LLM.

# baseline example

import os

import time

import openai

client = openai.OpenAI(

base_url="https://api.groq.com/openai/v1", api_key=os.environ.get("GROQ_API_KEY")

)

model = "qwen/qwen3-32b"

def llm_call(prompt):

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": prompt}],

)

return response.choices[0].message.content

def n_llm_calls(prompts):

responses = [llm_call(prompt) for prompt in prompts]

return responses

if __name__ == "__main__":

prompt = "Explain the tactical philosophy of {coach} in 200 words."

coaches = ["Pep Guardiola", "Jurgen Klopp", "Carlo Ancelotti"]

prompts = [prompt.format(coach=coach) for coach in coaches]

start_time = time.time()

n_llm_calls(prompts)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Time taken: {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

Now, we implement a version where the LLM calls are made asynchronously.

# Async llm calls

import asyncio

import os

import time

import openai

# you have to use async client or else this does not work

# I will explain later what is under the hood of AsyncOpenAI module

async_client = openai.AsyncOpenAI(

base_url="https://api.groq.com/openai/v1", api_key=os.environ.get("GROQ_API_KEY")

)

model = "qwen/qwen3-32b"

async def async_llm_call(prompt):

response = await async_client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": prompt}],

) # async operation must be awaited

return response.choices[0].message.content

async def async_n_llm_calls(prompts):

tasks = [asyncio.create_task(async_llm_call(prompt)) for prompt in prompts]

responses = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

# the two lines above schedule the tasks to be run concurrently

return responses

if __name__ == "__main__":

prompt = "Explain the tactical philosophy of {coach} in 200 words."

coaches = ["Pep Guardiola", "Jurgen Klopp", "Carlo Ancelotti"]

prompts = [prompt.format(coach=coach) for coach in coaches]

start_time = time.time()

asyncio.run(async_n_llm_calls(prompts))

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Time taken: {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

With the asyncio library, there are just four main changes to make:

- Use the async version of the client

openai.AsyncOpenAI, whereby itschat.completions.createmethod is non-blocking. awaitthe LLM call inside anasync deffunction.- Use

asyncio.create_task()to schedule the independent calls concurrently, andasyncio.gather()to await them all together. Wrap them within a higher levelasync deffunction. - Start the whole thing with

asyncio.run().

In one test run, the async version completed in 3.19s, compared to 9.82s for the non-async version, a ~3× speedup. Why the difference? As we are asking the autoregressive LLM for a pretty lengthy output, it takes some time to complete each request (about 3s). In the default version, the program waited for each LLM call request to be completed at the external compute and returned before firing the subsequent one, while the async version did not wait between the calls.

Nested async workflows

What if your program is a lot more complex? Let say you have many LLM calls invoked at multiple levels of a hierarchical function. Some of these calls may depend on each other, while others can run independently.

To make the most of Python’s concurrency model using asyncio, you can follow a layered, bottom-up approach:

- Start from the lowest-level async operation you are calling directly such as

async_client.chat.completions.create. Apply await expression and wrap in an async def function as shown earlier - Propagate upwards: As you move up the call stack, continue wrapping higher-level logic in

async deffunctions. Useawaitwhen calling your lower-level async functions, building an asynchronous call chain all the way to the top. - At any level where there are multiple tasks that are independent given the current states and inputs, use

asyncio.create_task()andasyncio.gather()to schedule them concurrently.

Here we show an example of such program that researches the profile of a soccer team with LLM.

### Function Hierarchy ###

# get_team_profile

# |- get_team_tactics

# |- get_key_player_profiles

# |- get_key_player_names

# |- get_player_profile

import asyncio

import os

import time

import openai

async_client = openai.AsyncOpenAI(

base_url="https://api.groq.com/openai/v1", api_key=os.environ.get("GROQ_API_KEY")

)

model = "qwen/qwen3-32b"

async def async_llm_call(prompt, task_marker=None):

start_time = time.time()

response = await async_client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": prompt}],

) # this is the operation we want to make non-blocking to others

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Time taken for {task_marker}: {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

return response.choices[0].message.content

async def get_team_profile(team_name):

team_tactics_task = asyncio.create_task(get_team_tactics(team_name))

key_player_profiles_task = asyncio.create_task(get_key_player_profiles(team_name))

team_tactics_response, key_player_profiles_response = await asyncio.gather(

team_tactics_task, key_player_profiles_task

)

return {

"team_tactics": team_tactics_response,

"key_player_profiles": key_player_profiles_response,

}

async def get_team_tactics(team_name):

prompt = "You are a soccer tactical analyst. In 300 words, explain the tactical style of {team_name}."

return await async_llm_call(prompt.format(team_name=team_name), task_marker="team_tactics")

async def get_key_player_profiles(team_name):

prompt = """You are a soccer scount. do some brief thinking and name the 5 key players of the team {team_name}.

Respond in the following format:

## format

Thoughts: <your thoughts here>

Players: <list of players here, separated by commas>

"""

response = await async_llm_call(

prompt.format(team_name=team_name), task_marker="key_player_names"

)

key_players = response.split("Players: ")[1].split("\n")[0].split(",")

player_profile_tasks = [

asyncio.create_task(get_player_profile(player)) for player in key_players

]

player_profiles = await asyncio.gather(*player_profile_tasks)

return {player: profile for player, profile in zip(key_players, player_profiles)}

async def get_player_profile(player_name):

prompt = "You are a soccer scout. Provide the profile of the player {player_name} in 30 words."

return await async_llm_call(

prompt.format(player_name=player_name), task_marker="player_profile"

)

if __name__ == "__main__":

start_time = time.time()

output = asyncio.run(get_team_profile("Liverpool"))

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Total Time taken: {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

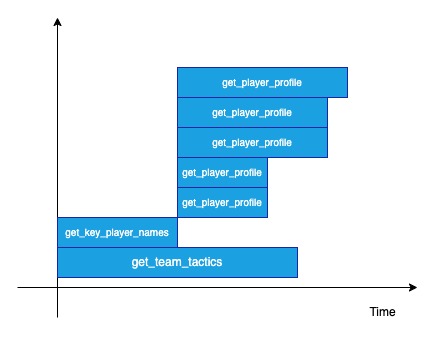

The actual LLM call counts and dependencies are as follow:

get_team_tactics: LLM call x 1 (independent)get_key_player_names: LLM call x 1 (independent)get_player_profile: LLM call x 5 (dependent onget_key_player_namesoutput, but independent from one another)

The output of the program:

Time taken for key_player_names: 1.46 seconds

Time taken for player_profile: 1.07 seconds

Time taken for player_profile: 1.07 seconds

Time taken for team_tactics: 2.93 seconds

Time taken for player_profile: 1.79 seconds

Time taken for player_profile: 1.79 seconds

Time taken for player_profile: 2.19 seconds

Total Time taken: 3.85 seconds

The total time taken is roughly equal to the time taken for get_key_player_names + longest time taken for get_player_profile. The timeline of execution can be roughly thought of as depicted in this diagram below, where each bar is the timespan of the respective function call:

The ingenious thing about asyncio is that, in terms of the way we have to write the program, it is just some syntactic sugars away from our default synchronous implementation. Yet, it is so powerful in optimizing the control flow. (Imagine what a mess it would be to do that with multiprocessing … more about that later)

What’s happening under the hood

Now let me introduce you to the key pieces of implementations that enable the behaviour described above.

Yield control with generator

In reality, when using asyncio, your client machine is not executing all independent task instructions simultaneously. There is only a single thread that is running your code, instruction by instruction. One core piece that enables multiple tasks to make progress seemingly in parallel is the generator mechanism.

Many of you are familiar with the implementation of generatorsin python. These functions are often defined with yield. A generator-function returns a generator object when called. That object implements __next__() which runs the function’s body until the next yield.

yield = “giving control”. Whenever execution hits a yield, two things happen:

- A value is “yielded” back to the caller (e.g. to

next()or to aforloop), - The function’s local state is frozen at that point, so on the next invocation it resumes right after the

yield.

def count_up_to(n):

i = 1

while i <= n:

yield i # ① send `i` back, pause here

i += 1 # ② resume here on the next next()

gen = count_up_to(3) # gen is a generator object

print(next(gen)) # → 1

print(next(gen)) # → 2

print(next(gen)) # → 3

# next(gen) now raises StopIteration

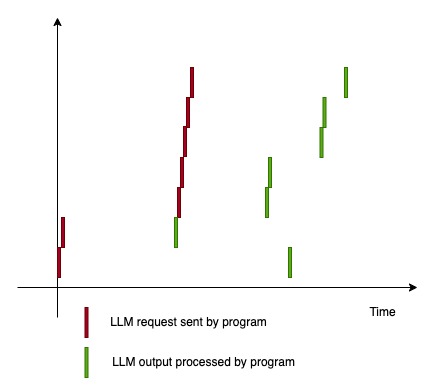

When the method async_client.chat.completions.create is awaited, in the lowest level, there is a generator object getting iterated. This generator is implemented such that it yields after the http request is sent (while waiting for request to be fulfilled). This is a critical point that allows the program to pause the execution there, go do other stuff, and comes back to resume the execution when data is returned.

So in reality, the execution timeline looks closer to this:

Bubbling up yields, bubbling down controls

Now that you have a sense of the “pause and resume” mechanism, I want to talk about the way asyncio library is written that allows you to propagate the await/ async def layers as shown earlier. We will begin by explaining how to chain generators.

Let’s say we want to nest a subgenerator within a generator, and our main program can only directly touch the outer generator. Think about how we would have to write the program such that it can still step through the yielding points in subgenerator, and get its return to bubble back up to the outer generator.

def subsubgenerator():

yield "subsubgenerator yield point"

return 1

def subgenerator():

a = subsubgenerator()

yield "subgenerator yield point"

return a + 1

def generator():

a = subgenerator()

return a + 1

def main():

g = generator()

while True:

try:

print(next(g))

except StopIteration as b:

print(b.value)

break

main()

The above will not work because when we call subgenerator() within the generator , it only returns you an iterator instance, which we then have call next on to step through the yields. We would have to add a block like this within the generators:

def generator():

# code to instantiate subgenerator, iterate and catch return value

temp = subgenerator()

while True:

try:

yield next(temp)

except StopIteration as value:

a = value.value

break

return a + 1

The introduction of yield from since python 3.3 makes things much easier. It takes care of the iterator instantiation, iteration, and return value catching under the hood. It allows you to write like below instead:

def subsubgenerator():

yield "subsubgenerator yield point"

return 1

def subgenerator():

a = yield from subsubgenerator()

yield "subgenerator yield point"

return a + 1

def generator():

a = yield from subgenerator()

return a + 1

def main():

g = generator()

# g.throw(Exception("test"))

while True:

try:

print(next(g))

except StopIteration as b:

print(b.value)

break

main()

Outputs:

subsubgenerator yield point

subgenerator yield point

3

With that, yield from takes care of bubbling up the yield point and the return from the innermost to the outermost generator, and also the bubbling down of next() from the outermost to the inner most generator.

Here I want to introduce 2 other operations that can be bubbled down with this construct - send and throw , the knowledge of which will come in handy later. send is a method to forward value to a generator + step the generator until its next yield:

def generator():

x = yield 1 # x will be assigned to the argument of mehod `send`

yield "got " + str(x)

g = generator()

print(next(g))

print(g.send(2))

outputs:

1

got 2

by nesting with yield from , you can send from the outermost to the innermost layer.

def subgenerator():

x = yield 1

return x

def generator():

y = yield from subgenerator()

yield "got " + str(y)

g = generator()

print(next(g))

print(g.send(2))

outputs:

1

got 2

when you do g.send(None) , it is equivalent to next(g) .

In similar fashion, throw allows you to forward exception from the outermost to the innermost generator when they are chained by yield from .

def subgenerator():

try:

yield 1

except Exception as e:

print("subgenerator caught exception")

print(e)

return 2

def generator():

out = yield from subgenerator()

yield out

g = generator()

print(next(g))

g.throw(Exception("forwarded exception"))

outputs:

1

subgenerator caught exception

forwarded exception

In short yield from mechanism enables a bidirectional delegation when we nest the generators.

Chaining awaitables

Now we are ready to unpack what is within the await expression and how the propagation of await expression + async def function works.

In Python, you can only apply the await expression on the objects that implemented the await protocol, and they are called awaitables. The await protocol requires 2 things:

- the object must implement the

__await__()method - the

__await__()method must return an iterator

The yielding point which dictates the “pause and resume” breakpoint typically hides within an __await__() method of an awaitable that is custom defined, in the deepest level of the propagation chain. Most of the time as a developer, you won’t touch the custom awaitables directly. Instead you start from a higher level awaitables imported from some other library (likeasync_client.chat.completions.create() , asyncio.sleep()).

As shown earlier, we commonly define wrapping functions using the async def syntax, and we name these functions the coroutine functions. Calling such a function returns a coroutine object. Internally, this object already implemented __await__() by default. As we will show you soon, it actually returns an iterator over the coroutine function body content, making the coroutine object awaitable by default.

Let’s reexamine what is happening when we did the propagation of await expression + async def coroutine functions with the example below:

import asyncio

import openai

import os

async_client = openai.AsyncOpenAI(

base_url="https://api.groq.com/openai/v1", api_key=os.environ.get("GROQ_API_KEY")

)

model = "qwen/qwen3-32b"

async def some_coroutine_func():

response = await async_client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": "tell me a joke"}],

)

return response.choices[0].message.content

async def parent_coroutine_func():

result = await some_coroutine_func()

In this case, the custom awaitables are hidden a few layers beneath the async_client.chat.completions.create which we do not touch directly. In the some_coroutine_func and parent_coroutine_func body, the code equivalents that are running under the hood are actually almost as follows:

# in some_coroutine_func

_llm__it = async_client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": "tell me a joke"}],

).__await__()

response = yield from _llm__it

# in parent_coroutine_func

_some_coroutine_it = some_coroutine_func().__await__()

result = yield from _some_coroutine_it

The __await__() methods of the coroutine objects are actually returning iterators which yield from lower level coroutine objects. We are thus able to nest the awaitables with await expression + async def coroutine similar to how we nest generators with yield from as shown in the previous section. We can rest assured that the bidirectional delegation of yield/return/error is taken care of. The scheduler then controls the execution of nested awaitables by just directly interacting with the top level coroutine object with the methods of send and throw. What a brilliant design pattern at work!

NOTE:

As of Python 3.13, yield from is actually not explicitly written at python code level within implementation of the await mechanism, however the underlying execution at bytecode level is actually identical. You can run the below to verify:

import asyncio

import dis

async def some_coroutine_func():

await asyncio.sleep(1)

return 1

async def parent_coroutine_func():

x = await some_coroutine_func()

return x

def similar_parent_coroutine_func():

x = yield from some_coroutine_func()

return x

print(dis.dis(parent_coroutine_func))

print("****************")

print(dis.dis(similar_parent_coroutine_func))

Outputs in python 3.13 below: The only difference is that with the default await implementation, there is a GET_AWAITABLE operation vs GET_YIELD_FROM_ITER in the alternative implementation.

10 RETURN_GENERATOR

POP_TOP

L1: RESUME 0

11 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (some_coroutine_func + NULL)

CALL 0

GET_AWAITABLE 0

LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

L2: SEND 3 (to L5)

L3: YIELD_VALUE 1

L4: RESUME 3

JUMP_BACKWARD_NO_INTERRUPT 5 (to L2)

L5: END_SEND

STORE_FAST 0 (x)

12 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

RETURN_VALUE

11 L6: CLEANUP_THROW

L7: JUMP_BACKWARD_NO_INTERRUPT 6 (to L5)

-- L8: CALL_INTRINSIC_1 3 (INTRINSIC_STOPITERATION_ERROR)

RERAISE 1

ExceptionTable:

L1 to L3 -> L8 [0] lasti

L3 to L4 -> L6 [2]

L4 to L7 -> L8 [0] lasti

None

****************

15 RETURN_GENERATOR

POP_TOP

L1: RESUME 0

16 LOAD_GLOBAL 1 (some_coroutine_func + NULL)

CALL 0

GET_YIELD_FROM_ITER

LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

L2: SEND 3 (to L5)

L3: YIELD_VALUE 1

L4: RESUME 2

JUMP_BACKWARD_NO_INTERRUPT 5 (to L2)

L5: END_SEND

STORE_FAST 0 (x)

17 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

RETURN_VALUE

16 L6: CLEANUP_THROW

L7: JUMP_BACKWARD_NO_INTERRUPT 6 (to L5)

-- L8: CALL_INTRINSIC_1 3 (INTRINSIC_STOPITERATION_ERROR)

RERAISE 1

ExceptionTable:

L1 to L3 -> L8 [0] lasti

L3 to L4 -> L6 [2]

L4 to L7 -> L8 [0] lasti

None

The mastermind scheduler, task and event flag

Now would be a good point to finally introduce the mastermind scheduler that coordinates all asynchronous operations - the EventLoop . It’s the central scheduler that knows which coroutines are running and which ones are paused, and when each should resume. It is called the event loop because it is indeed a forever running loop that repeats a sequence of actions in each iteration (till a stop signal). For now, we will simplify and just assume it does the following in each iteration:

while True:

1. Some housekeeping on I/O readiness

2. Pop callbacks from a ready job queue and run

# (some callback executions may add more callbacks into the job queue)

In parallel, we introduce 2 python classes that it interacts with: Future and Task .

- A

Futureis a low-level event placeholder — it represents a result that’s not ready yet. It’s typically used to represent the outcome of an asynchronous operation like:- an HTTP request

- a timeout (

asyncio.sleep) - a socket read/write

- a subprocess call

- A

Taskwraps a coroutine and is responsible for driving its execution. It runs the coroutine step-by-step and stores the result or exception once the coroutine completes. It is actually a subclass ofFuturealthough their use cases are somewhat different.

Let’s walk through how an event loop operates an asynchronous operation from start to end, with a simple example here:

import os

import asyncio

import openai

async_client = openai.AsyncOpenAI(

base_url="https://api.groq.com/openai/v1", api_key=os.environ.get("GROQ_API_KEY")

)

model = "qwen/qwen3-32b"

async def some_coroutine_func():

response = await async_client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": "tell me a joke"}],

)

return response.choices[0].message.content

async def parent_coroutine_func():

result = await some_coroutine_func()

asyncio.run(parent_coroutine_func())

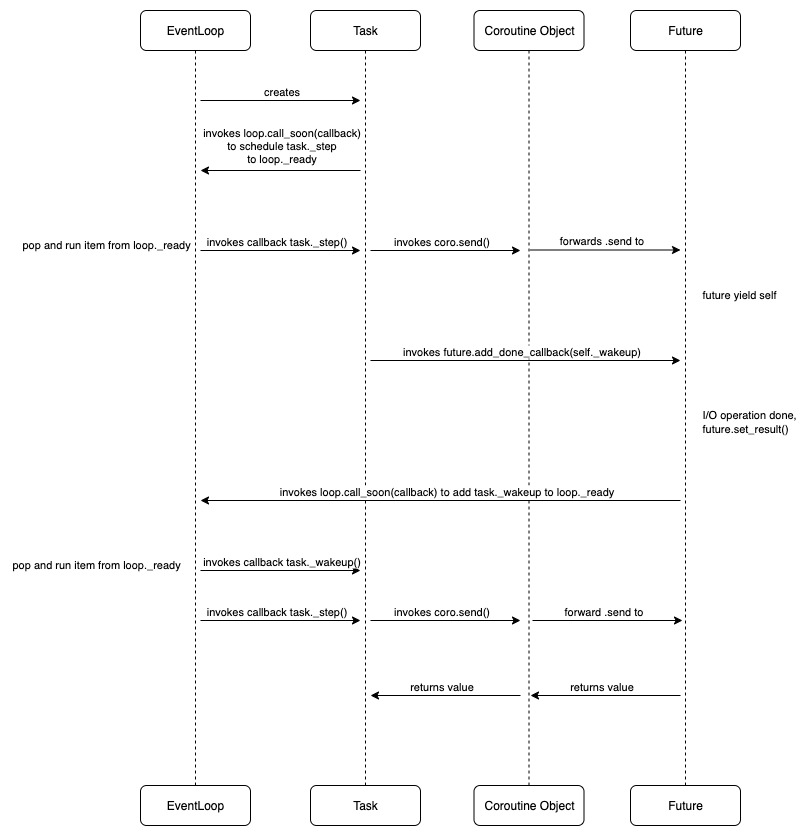

Here we spell out what is happening, step-by-step. (You may want to read it while referring to the next diagram):

-

When we call

asyncio.runon this object, an event loop is set up, and it does the below to create ataskto manage the coroutine object returned byparent_coroutine_func().task = asyncio.create_task(parent_coroutine_func()) -

When

taskis created, a callback to advance the task (task._step) is scheduled into a job queue calledloop._ready. The event loop goes throughloop._readyand executedtask._step. Insidetask._step(), it calls the method below to advance the coroutine execution:def __step_run_and_handle_result(self, exc): coro = self._coro try: if exc is None: # We use the `send` method directly, because coroutines # don't have `__iter__` and `__next__` methods. result = coro.send(None) else: result = coro.throw(exc) ...The task interacts with the top level coroutine object via

sendandthrowto forward the stepping and error injection. -

The coroutine starts running until it hits a yielding point. Typically somewhere in the second deepest awaitable, it hits a point which calls

await future(). TheFutureobject’s__await__()method then yields itself:def __await__(self): if not self.done(): self._asyncio_future_blocking = True yield self # This tells Task to wait for completion. if not self.done(): raise RuntimeError("await wasn't used with future") return self.result() # May raise too.The

taskwill then register a callback to thefutureyielded, telling the event loop what is to happen when thefutureis done:fut.add_done_callback(self._wakeup) -

The event loop now tracks the

futurewhich is our event flag. When the operation behind thefutureis complete, it is marked done viafuture.set_result()orfuture.set_exception(). (we will explain the mechanism to get informed on the I/O operation’s completion in the next section about I/O multiplexing). -

The update in the status of

futuretriggersfuture._schedule_callbacks(). Within this method, it callsloop.call_soon(callback)to schedule the wakeup call intoloop._ready. -

The event loop goes through the queue again in another iteration and calls

task._wakeup(), which then callstask._step()again to run the task until the next yielding point / return. -

When the coroutine finally hits

returnor completes, Python raisesStopIteration(value). Thetaskcatches this and callsself.set_result(value)(becauseTaskis aFuture). Whatever’s awaiting thistaskreceives the result.

Here is a diagram to sum up the above:

I/O multiplexing

We now need to throw in a couple more vocabularies — socket and file descriptor.

- socket: A software endpoint for sending or receiving data across a computer network.

- file descriptor: An integer handle the OS assigns to identify an open socket.

I/O multiplexing is a technique that allows a program to monitor multiple file descriptors simultaneously to see which are ready for I/O.

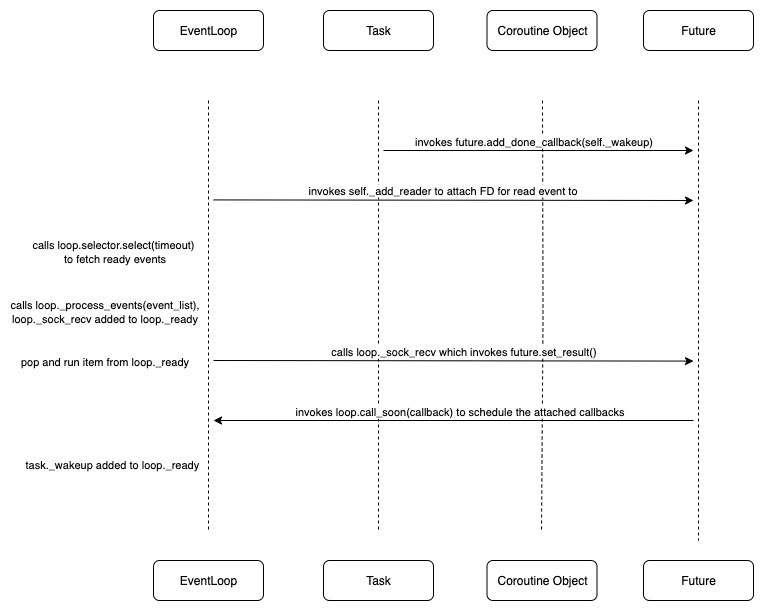

We shall revisit our example on the llm call and try to clarify how I/O multiplexing happens in openai.AsyncOpenAI.chat.completions.create after a request is sent. We mentioned that it will hit a yielding to yield a future object. Below is what actually happens in the event loop before the future is yielded:

fut = self.create_future()

fd = sock.fileno()

self._ensure_fd_no_transport(fd)

handle = self._add_reader(fd, self._sock_recv, fut, sock, n)

In particular, the last line registers the FileDescriptor (FD) for EVENT_READ via a low level object called selector .

In every event loop iteration, the selector actually performs a low level system call of select . This is the actual platform-level call provided by the operating system kernel that handles the I/O multiplexing. It does 2 things:

- blocks the thread until OS reports one or more FDs are ready (with a timeout)

- returns a list of ready FDs

When the OS reports the FD registered for EVENT_READ is readable within an iteration, the event loop will call loop._process_events(event_list). This triggers the method registered to the handle, i.e. self._sock_recv() to be added to the loop._ready queue. Within the same iteration, the event loop will pop this item from the queue and run. This method then calls future.set_result() within.

Below is the block which should be inserted into the previous diagram between the points that future is yielded and task._wakeup is scheduled:

selector.select and _process_events are the I/O housekeeping steps we referred to earlier within each iteration of the event loop. We now update the details on the actual order of execution within each event loop iteration:

while True:

1. Handle I/O: wait for sockets/fds (via selector.select)

2. Process events to add I/O callbacks to loop._ready

3. Check for expired timers (e.g. call_later / sleep) and move them to loop._ready

4. Run all callbacks that were in loop._ready

Task nesting and concurrent scheduling

Now we are going to talk about the last piece of puzzle that allows 2 or more tasks to make progress concurrently with asyncio . If you remember our little example with LLM call, the actual decisive code instructions written that allows parallel scheduling are the lines like below (Here we assume there is one LLM call within each llm_coroutine_func):

async def main_coroutine_func():

task1 = asyncio.create_task(llm_coroutine_func())

task2 = asyncio.create_task(llm_coroutine_func())

results = await asyncio.gather(task1, task2)

When you run this with asyncio.run(main_coroutine_func()), here’s what happens step-by-step:

-

The event loop and a main task wrapping the main coroutine object is created. a

main_task._stepis scheduled toloop._ready. -

The event loop runs

main_task._step()and executes:task1 = asyncio.create_task(llm_coroutine_func()) task2 = asyncio.create_task(llm_coroutine_func())Two new child tasks are created, with

task1._step()andtask2._step()scheduled toloop._ready, but they have not started yet. Whenmain_coroutine_func()reaches:results = await asyncio.gather(task1, task2)asyncio.gather(...)returns aFutureobject that waits for bothtask1andtask2. The main task yields thisfutureand is now suspended. -

In the next iteration, the loop then proceeds to run

task1._step()andtask2._step()fromloop._ready, until they yieldFutureobjects tied to respective file descriptors. At this point The LLM requests for respective tasks are sent. -

In the subsequent iterations, the event loop, via the selector, watches for the file descriptors for

task1andtask2simultaneously (with a timeout). If any of the file descriptors is ready within an event loop iteration, its correspondingfutureis updated, triggering the task to proceed as depicted in the earlier diagram within the same iteration. In reality, the 2 tasks may advance in interleaving manner, depending on how many yielding points there are and when their FDs become ready. -

As

task1andtask2complete, theFutureyielded byasyncio.gather()collects their results. Once all input tasks are done, it calls its ownset_result([...]). This triggers the scheduling of themain_task._wakeup(). -

The main task resumes till completion.

Follow-up readings

I also recommend you to read these robustly written posts on tenthousandmeters.com and RealPython for different angles of introduction on the subject if you are interested in more details about the related python internals. They also covered a few components and features that I skipped including the loop._scheduled priority queue and asynchronous comprehension. Shoutout to the authors as their write-ups definitely enhanced my understanding on the subject.

Asyncio vs multiprocessing

When we talk about concurrency technique, another library that comes into picture is multiprocessing in python. But how is asyncio actually different from multiprocessing and when to decide which is optimal to use?

Here I want to introduce you to the concepts of CPU bound vs I/O bound program. A program is considered CPU bound if the program will go fast when the CPU were faster, i.e. it spends the majority of time doing computations with CPU. On the other hand, a program is considered I/O bound if it would go faster when the I/O subsystem were faster. These programs could include network I/O tasks (wait for server response, stream data) where the bottleneck is external latency.

asyncio relies on a single thread in a single process to execute instructions sequentially. The programs that really benefit from it are the I/O bound programs which spend majority of time waiting for read/write operations to complete. asyncio coordinates other tasks to proceed while some tasks are waiting for the I/O operations. The step that is actually parallelized is the “wait”. If your program consist of doing 20 different long chain of computations, asyncio won’t help. The single thread has to be blocked to compute a single task at a time for each task to progress. On the other hand,multiprocessing is the library that allows you to create multiple processes to execute computations across multiple tasks in parallel.

Given the above, it could then seem to you that multiprocessing can also cover the cases that benefited from asyncio , i.e. we could spin up multiple processes to “wait” for I/O operations in parallel as well. However I would caution this decision has its limitations:

- In

multiprocessingeach process you spin up will take up memory as it is independently managed from the other. So there are only so many processes you can spin up until you exhaust the resource. Also, if you spin up more process count than the number of CPU cores, they are not actually going to be all running in parallel. Instead the system will “switch” between the tasks to execute them (akin to asyncio, albeit overhead cost is much higher in multiprocessing). - It is arguably harder to write multiprocessing well when you are dealing with a function made up of hierarchical operations, like the one we have earlier. You have 2 options but each comes with obvious disadvantage:

-

First option we can try to write in similarly natural manner, nesting another process pool within a worker. As daemonic process are not allowed to have child processes, you will have to use

ProcessPoolExecutorfromconcurrent.futures(which actually builds on top ofmultiprocessingbut with the process marked non-daemonic). Even then, it is hard to keep track of the number of processes created at each level, and they could grow exponentially in a complex function. Imagine we add more levels to the following example:import multiprocessing import os from concurrent.futures import ProcessPoolExecutor def inner(x): print(f"[Inner] PID {os.getpid()} - x={x}") return x * x def outer(x): print(f"[Outer] PID {os.getpid()} - x={x}") with ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=10) as inner_pool: results = list(inner_pool.map(inner, [x + i for i in range(10)])) return results def main(): with ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=5) as outer_pool: results = list(outer_pool.map(outer, [1, 2, 3, 4, 5])) print("Final results:", results) if __name__ == "__main__": multiprocessing.set_start_method("spawn", force=True) main() -

Option 2. To avoid the challenge in managing number of workers created, we could attempt to create only a single process pool. You may think of passing this pool into the lower level functions for inner job to be submitted, thus still writing with a “nestable” design pattern. But since

thread.lockcannot be pickled this will not work. This leaves us to have to spell out dependency from inner to outer layer, which is a hassle to write and read:import multiprocessing from concurrent.futures import ProcessPoolExecutor def inner(x): return x * x def outer(results): return sum(results) def main(): num_outer_tasks = 5 inner_range = 10 # 1. Prepare inner tasks (flat list with group tracking) inner_jobs = [(i, i + j) for i in range(num_outer_tasks) for j in range(inner_range)] # 2. Grouped results placeholder grouped_inner_results = {i: [] for i in range(num_outer_tasks)} with ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=50) as pool: # 3. Submit all inner jobs futures = [pool.submit(inner, val) for _, val in inner_jobs] results = [f.result() for f in futures] # 4. Group inner results by outer_id (based on original job order) for (outer_id, _), result in zip(inner_jobs, results): grouped_inner_results[outer_id].append(result) # 5. Process outer results with ProcessPoolExecutor(max_workers=5) as pool: outer_futures = [pool.submit(outer, grouped_inner_results[i]) for i in range(num_outer_tasks)] outer_results = [f.result() for f in outer_futures] print("Final outer results:", outer_results) if __name__ == "__main__": multiprocessing.set_start_method("spawn", force=True) main()

-

Turning synchronous function into async-friendly version

To create a native asynchronous method, you need to custom define the low level awaitables, typically including their yielding points and callbacks for advancing the task. Most of the popular libraries typically have these implemented such that you can invoke their high level coroutines directly e.g. as defined in openai.AsyncOpenAI.

Is there other convenient way to turn your synchronous function into async-friendly version without making low level changes? The answer is yes. There is an event loop method that allows you to submit a synchronous operation to a separate background thread via ThreadPoolExecutor . The event loop takes the result from the background thread and puts it into a special asyncio.Future, so your coroutine can await it just like any other async task.

Let’s modify the async_llm_call in our initial example program with the following, and you shall see a somewhat similar level of speed-up compared to using the default asynchronous openai client.

def llm_call(prompt):

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model=model,

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": prompt}],

)

return response.choices[0].message.content

async def async_llm_call(prompt, task_marker=None):

start_time = time.time()

loop = asyncio.get_running_loop()

result = await loop.run_in_executor(None, llm_call, prompt)

end_time = time.time()

print(f"Time taken for {task_marker}: {end_time - start_time:.2f} seconds")

return result

In Python, when you do multithreading, Python bytecode is not executed in true parallel across threads. This is because of the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), which allows only one thread to execute Python code at a time. However, multithreading still benefits I/O-bound tasks, because many blocking operations (like sleep or socket I/O) release the GIL while waiting. This allows other threads including the one running the asyncio event loop to continue executing. The operating system’s thread scheduler handles preemptive switching between these threads, enabling them to make progress in an interleaved way.

So what’s the catch here? Firstly, thread is more expensive in terms of memory. There are thus only so many threads (with arg max_workers) that you can practically create. Each job submitted will occupy one thread, and if you submit more jobs than the threads, they will be queued and wait until any of the currently occupied threads is released. Besides there is also more context switching cost: when the OS switches from one thread to another, it must save the current thread’s CPU state (registers, stack pointer, etc.) and restore the next thread’s state, making it less efficient than native task switching within event loop.

Nonetheless, the above method is still valuable if you are careful about the nature and quantity of submissions to the threads. At the very least It allows you to write your program in consistent design pattern if you are already using a lot of native asynchronous methods.

Summing up

To me, more than just a concurrency tool, asyncio is a programming paradigm because of the ease at which it allows you to structure your code. It gives you high concurrency with the readability and modularity of synchronous code, that’s the real power. I have included all the examples illustrated in this github repo. Hopefully this piece could be of some help the next time you want to optimize your scaffolded LLM system. If you notice any error or have feedback, feel free to leave a comment or reach out to me.

Carve-out

I named this post after reading a book that shifted my perspective on how I should grow in my area of interest. When I was younger, I often optimized for other people’s opinions. That mindset led me down paths away from my true passions, chasing shortcuts just to appear like a “winner”. But now I’ve come to realize that the only race that truly matters is the one against myself.

“For me, running is both exercise and a metaphor. Running day after day, piling up the races, bit by bit I raise the bar, and by clearing each level I elevate myself. At least that’s why I’ve put in the effort day after day: to raise my own level. I’m no great runner, by any means. I’m at an ordinary – or perhaps more like mediocre – level. But that’s not the point. The point is whether or not I improved over yesterday. In long-distance running the only opponent you have to beat is yourself, the way you used to be.” ― Haruki Murakami, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running